For their September 2017 issue, Connecticut Magazine sat down with our founder, Tim Byrne, who for over two decades has lifted machines, furniture, and other abandoned objects out of the flame and ash of America’s manufacturing heyday and—like a phoenix—given them new life. The author writes “In more recent years, perhaps because of anxieties about what has been lost, the principles of design that governed this great boom in American manufacturing have become fresh again. There is a new American aesthetic It’s been called industrial chic, or vintage industrial, and it appeals to collective memory, a vision of the past that is part of the DNA of a place like Waterbury. You’ve seen it at Restoration Hardware. You see it anytime you go into a third-wave coffee shop or brewery tap room with exposed brick and pipes girding the ceiling. It’s an aesthetic hints at the heat, the smell, and the roughness of the industrial processes, blended with the clean, Scandinavian smoothness of current tech-inspired design.” And “Tim Byrne, an Irish immigrant who is equal parts carpenter, revivalist, design guru, and mad scientist, was at the vanguard of this aesthetic innovation.”

The article, aptly titled “Industrial Revolution,” rightly asks, “When was the last time you had an item repaired to extend its life?” and continues by observing that “As Byrne strolls through his space, he points out the functionality of unreconstructed machines in the raw-materials section. What looks to the untrained eye like pure scrap, to Byrne is pure art. His mind cuts through the cobwebs and dust that coats the old machinery, preferably pre–World War II American, that he picks up at auctions or scrap yards. He sees not ruins, but something clients like Bono, Meg Ryan, or Bruce Springsteen might have in their homes.”

“Another central feature of Byrne’s furniture design is the preservation of a pieces functionality.” When it comes to steampunk movement Byrne says, “I really don’t buy into it, because I think in steampunk they add things. We try and keep it as real as possible. If it has gears and chains on it, it works.” We do our best to make a careful distinction with what we do here—where mechanical functional is inextricably linked to the aesthetic form.

Another great observation is the way Tim uses his tape measure “for pointing as a school teacher might use a stick.” Part of appreciating the vintage-industrial style is knowing what to look for. It is a way of seeing. “Byrne has difficulty fully explaining a concept without pointing to a design element on a piece that he’s already done or is envisioning. Such are the mechanics of the furniture designer’s mind.”

To continue reading, visit Connecticut Magazine.

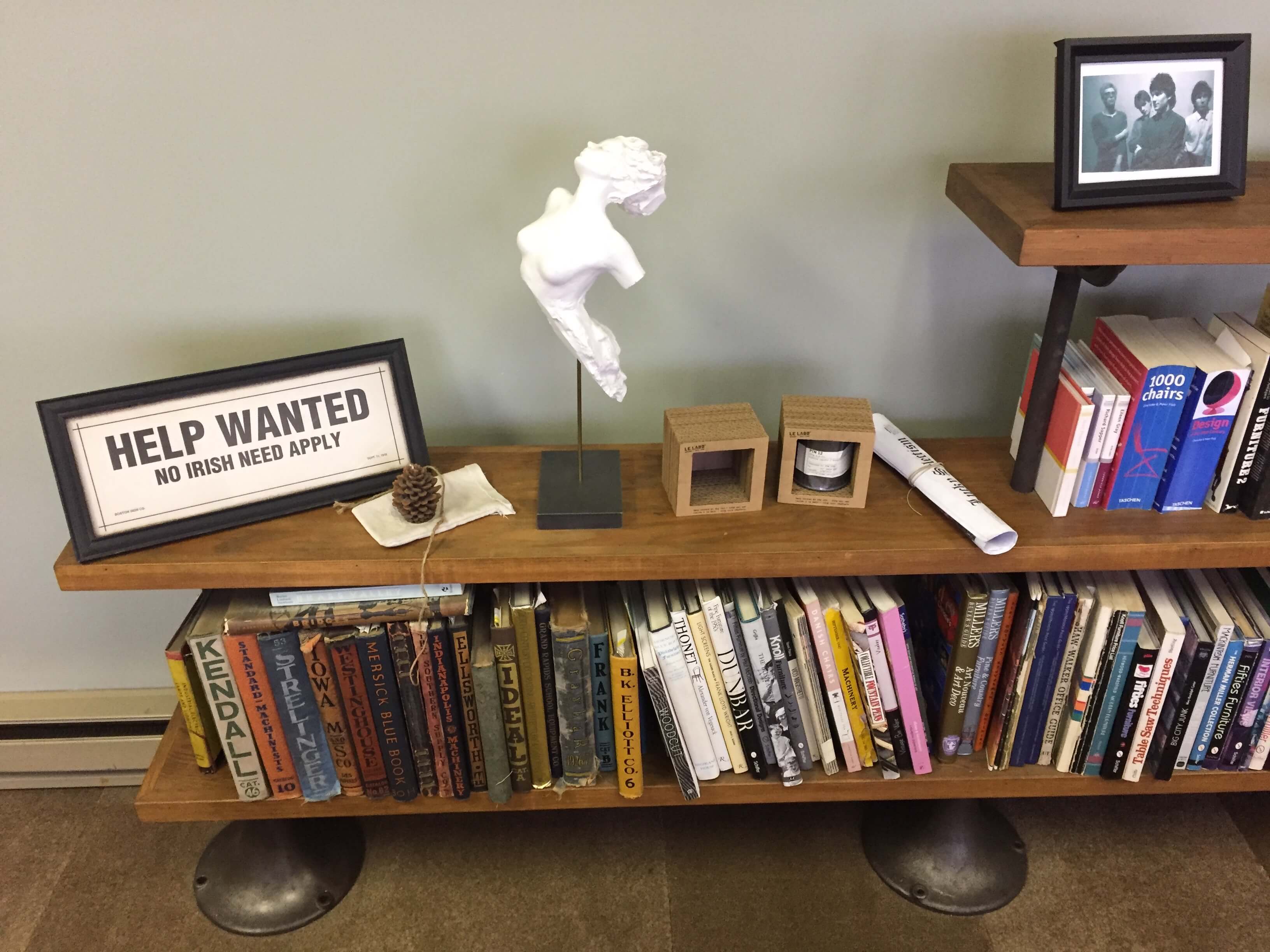

Describing our floor here at the historic Oakville Pin Company building, the author writes, “The 30,000-square-foot space is divided into several sections, each representing a different part of the Get Back process. One side of the former factory has raw materials, housed in a gaping hall. The cavernous room is packed to the walls with old book presses and other machines with cranks and wheels we have long lost use for. Another section houses the wood shop, where Byrne and eight or so employees manufacture wood furniture. On the other side of the floor is a magnificent showroom, where Byrne’s finished pieces are displayed.”

The author noticed that “In the foyer of his shop there is a framed antique sign. ‘NO IRISH NEED APPLY,’ it reads.” capturing Tim’s indelible Irish humor.

Asked the name of a particular piece, in which a wheel and a chain are used to adjust the height of a massive glass surface, he replies dryly: ‘a table.’”